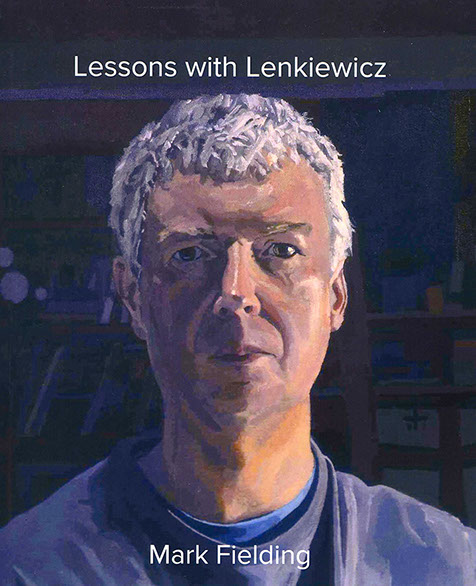

Publications - Lessons with Lenkiewicz

I have compiled a record of my lessons with Robert Lenkiewicz. The illustrated book is available to buy as a soft cover high quality edition for £18 incl £3 p&p. Please send a cheque payable to Mark Fielding to the address on the contact page.

Here's an extract to give a taste of the contents of the book.

Introduction

Many people have been interested in the life and work of Robert Lenkiewicz. My interest in Robert is built on my relationship with him as a teacher. I did not know him well in any other capacity. I offer this short book as a record of my experience of being taught to paint by Robert. The process of writing has given me the opportunity to reflect on the impact he has had on my artistic outlook beyond the technical nuts and bolts of painting itself. The book is not a ‘how to paint’ guide. It merely charts my experience of his teaching. After all the teacher-pupil relationship is partly dependent on what the pupil has to offer.

The book has been made possible because I kept a contemporaneous record of my lessons with Robert. I would record details of the lessons in the evening on the day and was able to remember his vivid turns of phrase and the points he made to me. The record is neatly divided into each meeting we had. The other record I have are the paintings themselves which represent the exercises set by Robert, either as homework or painted during the lessons. I still have all the 12” x 12” boards to refer to.

I have therefore been able to illustrate each section of the text with the appropriate painting. I have expanded the notes from the perspective of 2011, some thirteen years since I first met Robert.

The First Meeting: 25, The Parade, The Barbican, Plymouth, 20th December 1998.

Let me explain how I met Robert. In 1994 I moved to the area and took up a job as a loss adjuster dealing with insurance claims. It wasn’t long before I was dealing with a theft of one of Robert’s paintings. The painting itself was a portrait of a girl. I had to find out its value to establish how much to pay out under the policy. I asked around who might know such information and was given Francis Mallet’s name at the White Lane Gallery. I called him and discussed the matter and that was that. Sometime later, I visited his gallery and showed him some photos of my work. Diane Nevitt, his partner, was also there. Francis asked me how much I painted and I said ‘a lot’. When asked if I would like to be put in touch with Robert Lenkiewicz with a view to being taught by him, I readily agreed.

This then set the ball rolling. Francis gave me Robert’s number. He said he would tell Robert to expect my call. I duly called him and he asked me to call someone called Yana to arrange a meeting. After several calls with Yana, the meeting was arranged for 20th December 1998. I was not looking to be taught at this stage in my life. I was mostly self-taught and had developed simply by painting consistently over many years. Part of me was cynical as to what I could gain from his teaching. I wasn’t particularly knowledgeable about Robert’s work or life, although I was aware of him.

I had never been to the studios at 25, The Parade on the Barbican in Plymouth before. I had only looked through the window at displays of books and paintings. I entered with my portfolios and went up a small and dark staircase to find cavernous studios at the top. There were canvasses everywhere. Some were extremely large. I met Yana, who ’phoned Robert to say I had arrived. After a while I was taken downstairs and [was] shown into a room where Robert was sitting in an ornately carved chair. The room was a library. I don’t think Robert rose from the chair to shake my hand. He remained seated throughout. This could not be described as an informal encounter. Nevertheless, Robert welcomed me in and I laid the portfolios in front of him and sat down.

When asked to talk about myself, I described my life history, where I was born, where I grew up, my university days in Exeter and my career. I then back-tracked and described my life in terms of art. I told him I had studied art at A-level and then had gone on to study law. In my gap year I had travelled widely and had discovered portraiture while working in a summer camp in Texas, to keep boredom at bay. While at Exeter I discovered myself artistically: I established a Visual Arts Society, ran life classes and painted on the Exe estuary. I also mentioned that I had been a member of the print workshop at Gainsborough’s House in Sudbury, Suffolk, and had produced a number of prints.

Robert listened patiently. When I had finished, he asked me how much of my time was spent working. I explained my job was nine ’til five and that when I got home I spent a couple of hours with my sons, Simon, then aged four and Sebastian, two. Once they were in bed I was free to paint. He asked me whether my wife Claire was supportive of my painting. I said she was and Robert said that was fortunate.

He then asked me what I wanted. This was quite difficult as I wasn’t really looking for a teacher. I said I didn’t know, which in retrospect, was not a great response.

Robert asked me to show him my work. I had brought work drawn almost entirely from life. Many were life drawings in pastel and watercolour. I had also included a series of watercolours painted in Turkey a few years earlier. Finally, there were some etchings. Robert looked at them silently without comment and I then placed them all back. I do remember he spent a particularly long time looking at an etching drawn from my imagination (see fig 1). I wish I knew what he found so arresting in this image.

Robert then asked me, “What is tone?” I answered, “Light.” He wanted more. I said, “Light and dark.” “Why pastel?” he enquired. I replied “to paint from dark to light,” as I was using dark papers. And that was that.

He then asked me which two artists I liked. I replied Klee and Ken Kiff. I also mentioned that I admired Nolde’s watercolours and Whistler’s etchings and …Gainsborough. Robert commented that Gainsborough had painted some weak portraits. He also mentioned ‘Joshua Sloshua’, presumably referring to Joshua Reynolds. When, many years later I had the opportunity to visit a large exhibition of Reynolds’s work in Plymouth, I had to agree with Robert. I found the paintings on the whole, second rate.

I knew that Gainsborough had painted by candlelight so I asked Robert about this and the effect that this would have. He said that it encouraged tonal painting. Robert then became more expansive and talked about an artist who had a vellum box containing 500 candles hung from the ceiling to create light. He praised the success of artists such as El Greco and Titian. The former had had his own orchestra to play for him while he worked in Toledo. Robert saw artists in heroic terms.

Robert’s mind turned to the notion of the provincial artist. We both shared the experience of starting life in London and ending up in Plymouth. He said there was no need to be in a big city. He referred to the 17th century Dutch painters who lived in the country. “It was important to be in the right place for you.” He exploded the myth that you need to suffer to be an artist, that there was some kind of formula. “Soutine lived in shit, painting fly-covered skeletons and created great art, but this was not essential to create great art.